The majority of screenwriting applications (such as Final Draft) will give you the option to add a transition to the end of a scene. The most common transition to use is; CUT TO:

However, you shouldn’t constantly use the Cut To transition for the end of each scene. In fact, most writers use it sparingly, if not at all. But let’s look at when this transition is put to best use.

Good transitions should convey information, and if they are put to good use, the screenplay will read smoother.

CUT TO Examples

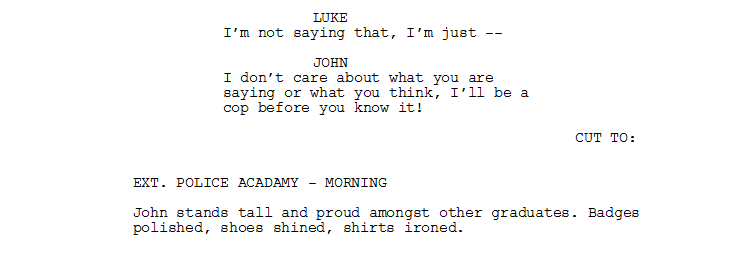

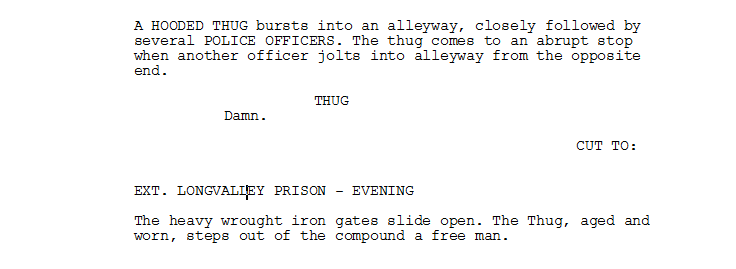

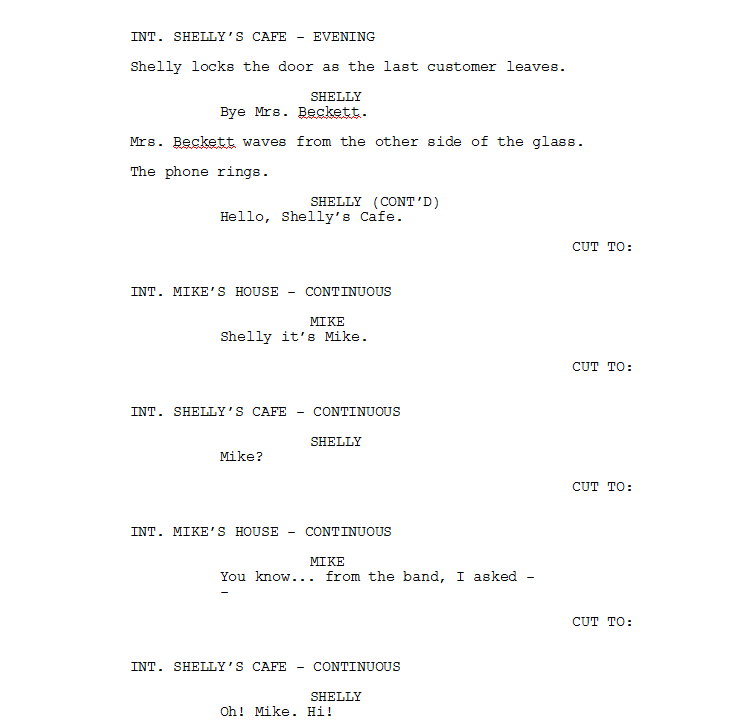

Example One.

Or

The best transitions are the content-based ones. Why is that? It is because the transition can tell us a story without showing us another 5 minutes of expositional content. We can make assumptions based on the intervening activity. We know that John became a cop like he said he would, and we also know that the thug served a lengthy jail sentence.

Using CUT TO For A Passage of Time

When else is the CUT TO transition an excellent to use? Well, quite often, in screenplays, we need to convey that a passage of time has passed. In the 50s & 60s, a common way of visually showing that time was passing was with a montage of shots dissolving into each other.

A dissolve cut (a transition that screenplay software supports) is often used to display a change of time or location. Quite often, filmmakers would dissolve multiple cuts to show a long period of passing.

But we can do better. Using the notion that content-based cuts are better than normal cuts, let’s look at what we can do.

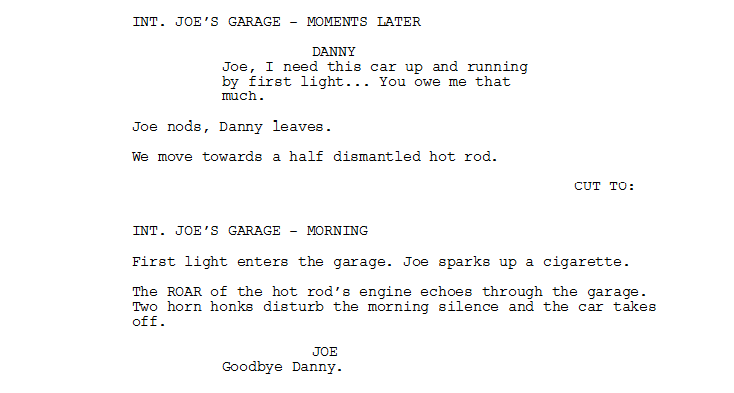

We know he finished working on the car, and Danny was gone at first light. We didn’t need to see him fixing the car, we didn’t need to see Danny leaving, but we knew all this took place because of an element included in the scene, in this case, the sound of the car. Let’s break this down into bullet points to illustrate the point further.

- Danny needs his car fixed.

- He needs it fixed by the morning.

- We see the dismantled car.

- We then cut to Joe lighting a cigarette with the morning light entering the garage

- The car’s engine echoes throughout the garage.

Right here, we have a visual and auditory link to Danny’s dialogue. The morning light and the now-working car. Believe it or not, our brains are smart enough to piece these bits of information together and work out that Joe has fixed the car. Joe then says, ‘Goodbye Danny’ for clarification.

This is not a rule you must follow; however, it allows us to omit a few useless shots and saves production time. After all, time is money.

Nevertheless, you must clearly show the element that signifies the time change, whether visual or auditory, as it will leave them confused. Just look at the controversial scene from The Dark Knight Rises where Bruce Wayne is suddenly back in Gotham with no explanation on how he got there when he was near enough paralyzed halfway around the world. It sparked internet debates for years to follow.

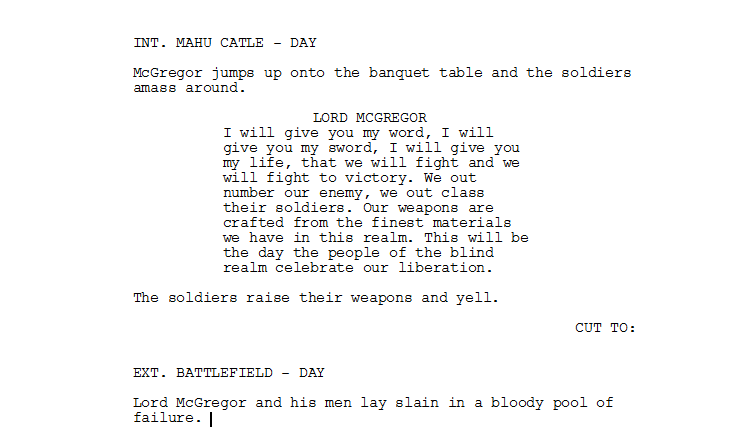

Using CUT TO For Irony

Finally, we will look at the comic transition. This is where we juxtapose the current scene and cut to another displaying a stark opposite of the information given to us in the first. It’s usually used for comedic effect even if the film isn’t a comedy.

So there we have a few methods where the CUT TO transition is put to good use.

Remember, writers use the CUT TO transition sparingly; if your script looks like the following, the transition is not being used correctly.

For more articles on writing, check out the following