Exposition; is the insertion of relevant background information within a story, such as information about the setting, characters’ backstories, prior plot events, historical context, etc.

The most common and sometimes the most controversial method to deliver exposition is through dialogue. Controversial because it can often feel contrived and sound unnatural. On paper, it would look something like this;

This extract gives us direct information about the character Gary. As the audience, we haven’t seen this information or discovered it ourselves. Instead, this information was given to us by a character whose sole purpose was none other than to speak those lines at that moment in time. By no means is this wrong, and sometimes it’s necessary to disperse information like this, but at best, too much of this can kill your script.

The audience paid to go on a journey, and when the action stops, and they are spoonfed information, empathy for the character (or story) can cease to exist. However, exposition is a necessary aid in deploying facts to the story amongst the action. This scene from Lord of The Rings: The Fellowship of The Ring is entirely made up of expository dialogue:

- What is the ring?

- What does it do?

- Where did Bilbo find the ring?

- What has the ring done to Bilbo?

- How is Sauron alive?

- What will happen next?

These are just a handful of questions that are answered in this scene; Is this wrong? Not, there are not many other ways to present this information at this point in the story. The exposition is organically given; In certain genres, like a crime procedural, the dialogue will naturally be littered with commentary. The characters are in a position where it is their job to present the facts.

How To Use Exposition

The vast bulk of exposition is expected to be submitted within the first ten pages, roughly the first 10 minutes of the film. However, it’s easy to fall into the trap of having expository dialogue fall into every other scene. The audience wants to find out information through action, not drawn out explanations.

Listed below are a few methods that will help you with the placement of expository dialogue and limit its use:

- As mentioned above, in some genres, it’s almost impossible to avoid heavy expositional dialogue because of the show’s nature. If you need to give a lot of exposition, you could use a stock character that appears in a heady expository genre; a police officer, a teacher, a scientist.

- Make sure the protagonist is actively learning, rather than passively listening.

- Exposition doesn’t have to be a monolog, keep it short and concise.

- Remove any expositional dialogue that will be revealed organically later in the story.

- Wait as long as possible before delivering the exposition. Deliver it at a moment of dramatic tension for maximum impact.

Ernest Lehman, writer of North by Northwest and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Says;

“One of the tricks is to have the exposition conveyed in a scene of conflict, so that a character is forced to sway things you want the audience to know. As, for example, if he is defending himself against somebody’s attack, his words or defense seem justified even though his words are actually expository words. Something appears to be happening, so the audience believes it is witnessing a scene (which it is), not listening to expository speeches. Humor is another way of getting exposition across.”

Exposition can also be defined as the facts needed to begin the story. These can be (but are not limited to);

- The location,

- The main characters,

- The period

- The equilibrium

Suppose the audience is not given the fundamental facts needed to become invested in the story. In that case, they may end up not being invested at all, as the subconscious will be searching for the missing information.

Exposition Through Text

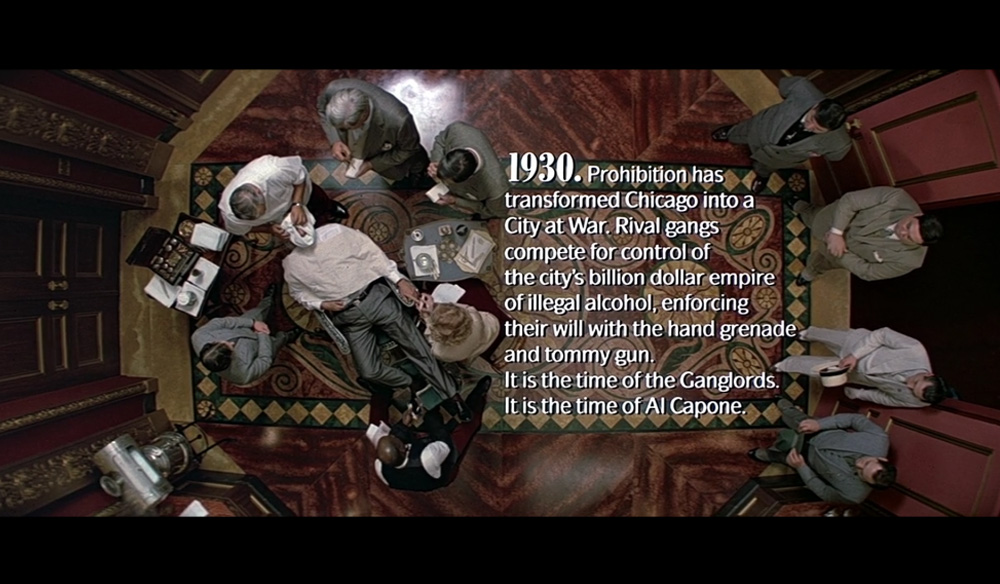

To avoid dull expository dialogue, filmmakers have sought different methods to introduce exposition as a film’s start.

In the 1987 film The Untouchables by Brian De Palma we are given exposition with a title card that simply states the political situation in Chicago.

Sometimes there is too much exposition to be given a title card, so we are presented with a title crawl. The award for the most recognizable title crawl is often granted to Star Wars — even if you have never seen a single Star Wars film, there is a good chance you will recognize the crawl below.

From the title crawl, we learn the relative history and context of a fictional universe, which would have otherwise bogged down an initial conversation. We are allowed to jump straight into the action with little expository dialogue.

Occasionally, when we are watching a film within a fictional world, the film can become littered with questions that need to be answered so the audience can understand the context of the fiction. Often it can work, but sometimes it may feel like a character is solely there to ask questions, so we as an audience, hear the answers.

Exposition Voice Over

Another form of creative exposition is to open a story with a voice-over. The narrator can feed us information while we are visually given separate material to digest.

In this clip from the 1994 film The Shawshank Redemption, we are given auditory information from Red. He introduces the year and the protagonist’s name. This informative narration is continued throughout the film and allows for natural conversation between the characters.

As stated in the list above, waiting until the climax of dramatic action is always an excellent place to insert exposition. The audience does not want information at this point; they crave it. The Harry Potter franchise would often reveal new information like this, usually in the form of a flashback.

Exposition is something your story requires, but too much can bog down your text with unnatural dialogue.